Yesterday the US Health and Human Services Secretary, Robert F. Kennedy Jr, dismissed an expert panel of vaccine advisers that has historically guided the federal government’s vaccine recommendations, saying the group is “plagued with conflicts of interest”.

He is expected to appoint new members soon – hopefully individuals with comparable expertise and free from financial and political conflicts of interest, however, that remains uncertain.

Vaccine hesitancy is on the rise in many parts of the world, a trend augmented by the COVID-19 pandemic and fuelled by misinformation spreading through online platforms. The consequences of declining vaccination rates are evident, with measles being a clear example.

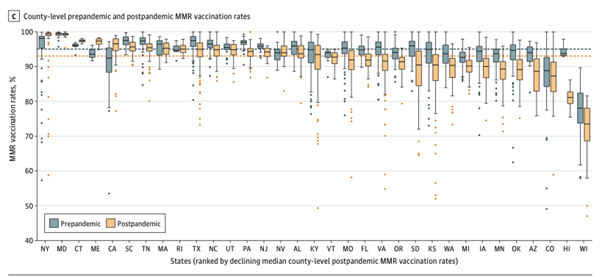

Currently, many eyes are focused on the surge of measles infections in Texas, occurring almost exclusively among unvaccinated children, and resulting in at least two fatalities so far. Last week, a figure published in JAMA Network, depicted measles vaccination rates before and after the pandemic across 33 States. See figure 1.

Figure 1: Measles vaccination rates before and after the pandemic across 33 states, published in JAMA Network.

In fact, the situation in Texas (TX) doesn’t appear that bad, although the coloured dots on Figure 1 reflect counties with vaccination rates below 85%. The ongoing outbreak in Texas demonstrates how isolated communities with low vaccination rates can enable widespread outbreaks. One can only imagine what might happen in Wisconsin (WI), shown at the right side of the figure.

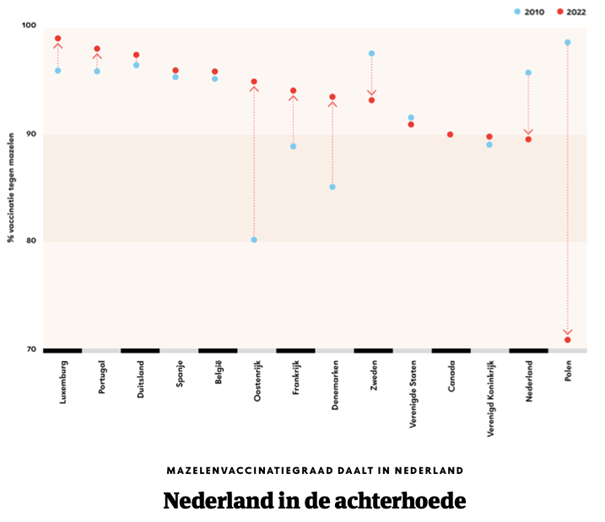

Measles vaccination rate EU

Then my eye caught the following figure (figure 2) in the Dutch medical journal, showing measles vaccination rates before and after the pandemic for 11 countries of the so-called “United States of Europe”, along with the US, Canada, and the UK. It showed that The Netherlands fell from a respectable leading position before the pandemic (with around 95% coverage) to a less impressive spot at the bottom, with coverage below <90% – lower than the US and most other EU countries.

The situation for Poland appears dramatic according to figure 2, with measles vaccination rates falling from a top position of 90% to 70%. If true, measle epidemics in Poland are almost inevitable, and every car with a Polish license plate visiting another country could represent a potential index case or even a superspreader vehicle.

Together, these data paint a grim prognosis of the likely resurgence of measles infections in Europe, just as we are currently seeing in Texas. In the Netherlands, this strengthens the case for adjusting our medical school programmes to include measles, an infection that I have seldom encountered in my professional life so far.

This morning, I spoke with someone who had been a young physician in South Africa in the 1990s. He recalled, “We had these terrible measles outbreaks, with wards completely occupied with sick kids, and 5 to 10 deaths per day.”

A brave new world – one that may no longer be restricted to fiction.

Brave New World is a dystopian novel by English author Aldous Huxley, written in 1931, and published in 1932.[3] Largely set in a futuristic World State, whose citizens are environmentally engineered into an intelligence-based social hierarchy, the novel anticipates huge scientific advancements in reproductive technology, sleep-learning, psychological manipulation and classical conditioning that are combined to make a dystopian society which is challenged by the story’s protagonist. Huxley followed this book with a reassessment in essay form, Brave New World Revisited (1958), and with his final novel, Island (1962), the utopian counterpart. This novel is often compared as an inversion counterpart to George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949).

Source: Wikipedia