Last week, this paper in Lancet ID generated heated (and mostly negative) discussions on X, but I suspect that selection bias may have had a role in that. What was (and was not) investigated? And how?

The study aimed “to do a comparative evaluation of both acute and long-term risks and burdens of a comprehensive set of health outcomes following hospital admission for COVID-19 or seasonal influenza.” The researchers did this by creating two different groups: patients hospitalized with COVID-19 (1, n=81,000) or with influenza (2, n=11,000), and then counted what – subsequently – happened to them (the endpoints) and compared those (comparative evaluation). Obviously, the groups differed, e.g., in their reason for admission and in time (COVID-19 during the pandemic and influenza in a period 3 years before that). Thus, the researchers attempted – based on available information at the time of admission about each person’s health and risk on outcomes – to equalize the groups as much as possible in order to make the infection (COVID-19 or influenza) the only difference.

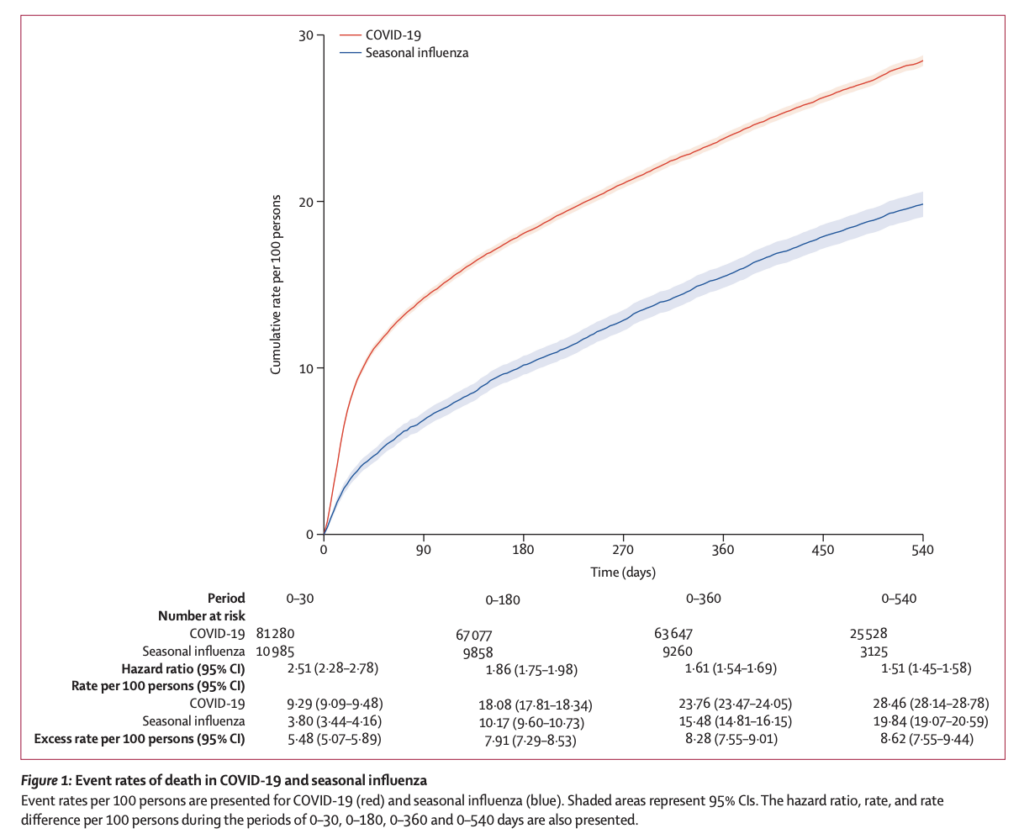

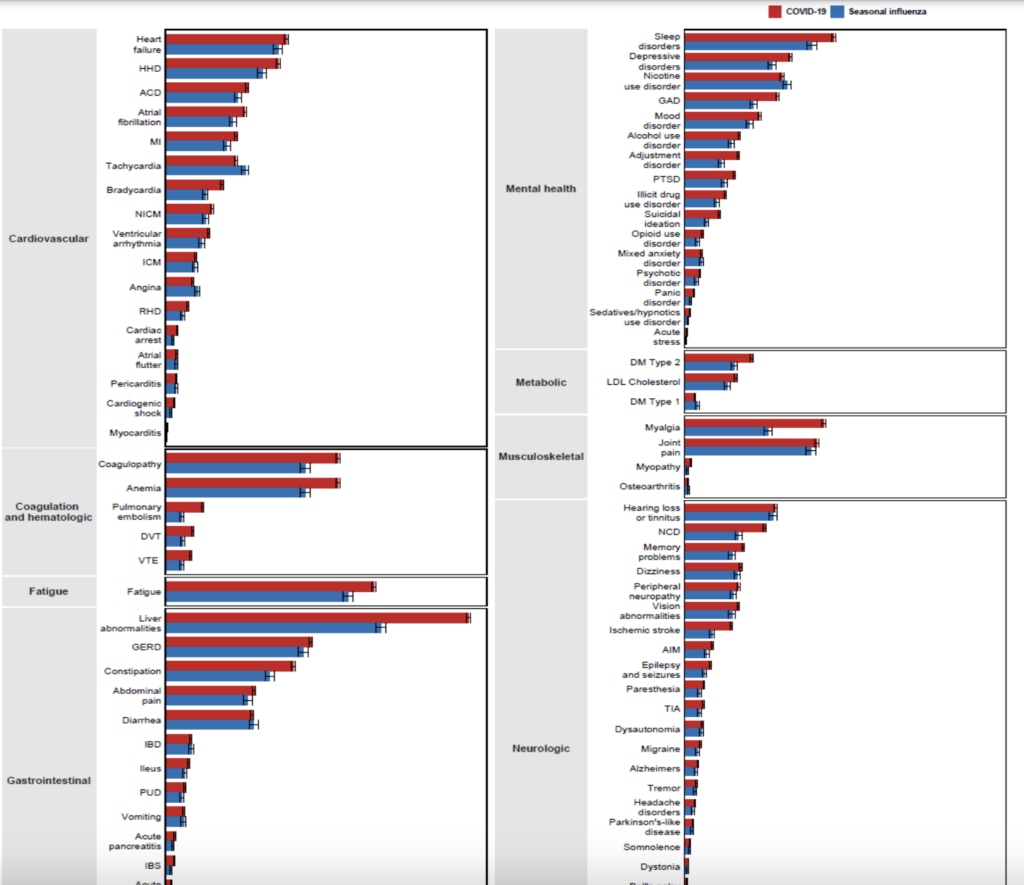

Persons reporting endpoints were not part of the study team; they were producing the healthcare bills from hospital health records, which should include all complications and events that occurred after being hospitalized. That procedure/accurateness may change over years, e.g., through higher awareness for some outcomes (during pandemic?), which would introduce bias for outcomes. Yet that also seems less likely regarding death. Death rate was higher for COVID-19 and mainly – as one would expect – in the acute phase: see angle of red compared to blue line (Fig1). Thereafter, both lines climb more or less in parallel, reflecting much smaller differences in death rates (although still somewhat higher for COVID-19). Other endpoints also mainly occurred in the acute phase, but with more comparable rates in both groups. In general, again, higher in COVID-19, but absolute differences were relatively small (Fig2). Statistically significant, but that is not necessarily equal to clinically relevant.

Is this study valid? To a large extent, yes. Obviously, the groups were different (for a good reason) and attempts for adjusting for other factors influencing the occurrence of endpoints were extensive but may never be perfect (as acknowledged). To me, it is shown convincingly that the differences in death rates in the acute phase are more likely caused by the infection types than by other determinants. I’m less convinced, though, regarding the “softer” endpoints with much smaller differences.

Is this study generalizable? Yes, to a similar population (American men of age). Whether this all applies to other countries or to infected people not needing hospitalization remains unknown.

My take: If you were an “American of age” hospitalized with COVID-19, your risk of death in the short-term was considerably higher than if admitted with influenza before the pandemic. And if you survived the acute phase, the risk of long-term complaints was considerable for both infections, and perhaps somewhat higher after COVID-19. The study shows that long-term complaints after infection are not exclusively associated (and may be not increased) with COVID-19. Yet as so many people had COVID-19 in such short time – it explains the burden the disease created, but it also suggests that an effective treatment for long/post-COVID may also be effective for other post-“infection complaints”.